By Manya Bhasin

March 5, 2024

How Does Your Little One Hear the World?

When someone is singing to a child, does the child think about song as serving a different function than speech, or do kids not really differentiate spoken from sung information?

LAMA Lab’s mascot listening to music. Image from LAMA lab.

Children are new to this world and each interaction brings something novel to investigate. Naturally, because we use language and music for communication and cultural identity, children are constantly surrounded by people talking and singing. But how does your little explorer actually understand these sounds? Dr. Christina Vanden Bosch der Nederlanden and a team of researchers from the US and Canada asked whether children can tell apart speech and song in a recent study. That is, when someone is singing to a child, does the child think about song as serving a different function than speech, or do kids not really differentiate spoken from sung information?

In undertaking this new line of inquiry, the team surveyed children as young as four years old to students in university. They found that, when describing how speech and song are different, children between the ages of four and seven thought that songs were faster and louder than speech, but older children and adults did not. This means that little kids are still learning exactly how song differs from speech.

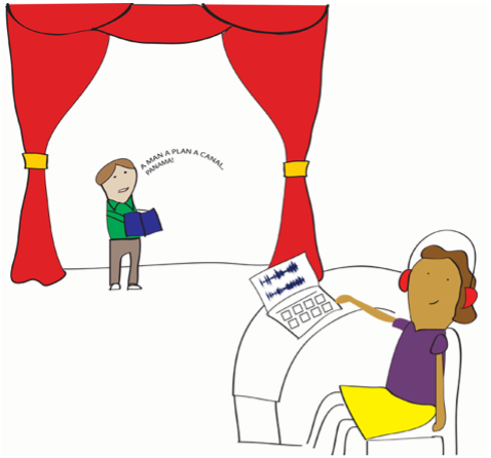

The researchers went a step further to understand whether children could categorize sounds as belonging to a musical or a play, as another way to see whether kids knew the difference between speech and song, but perhaps just couldn’t verbalize it well. The team had participants listen to audio files that (i) clearly sounded like speech, (ii) clearly sounded like a song, or (iii) were ambiguous and could be categorized as either speech or song. The children were given a scenario in which Frankie, a sound engineer, had mixed up the speech and song audio clips of a play and a musical. The children needed to sort out the audio into either speech or song—adults also followed this task in a similar manner.

The children were given a scenario in which Frankie, a sound engineer, had mixed up the speech and song audio clips of a play and a musical. The children needed to sort out the audio into either speech or song—adults also followed this task in a similar manner.

Example audio files participants were asked to categorize in to speech or song. From LAMA lab.

Example images shown to participants: Frankie recorded the files for a play but accidentally them up! Images from LAMA lab.

The researchers found that all age groups could correctly recognise the sounds that were “clearly song” better than the other audio files. Yet, four-year-olds struggled the most out of all the age groups. Researchers also found that the youngest age group was more likely to call an ambiguous sound “song” than other age groups, suggesting that they are still learning what features make something a song.

The researchers concluded that the accuracy for speech and song improves with age, and actual adult-like proficiency for music and language differentiation happens at ages eight to 12. Dr. der Nederlanden said that, before the age of eight, “[Children] are still learning how to describe it in their own words, but even perceptually, they are still learning which acoustic features are key to understanding what makes speech sound like speech and what makes song sound like song!”

The children were asked to place the audio files into “musical” and “play” categories based on whether the files were song or speech. Images from LAMA lab.

But why were Dr. der Nederlanden and her team interested in speech and song differentiation? In a real-world context, sounds can be very ambiguous and we have to use our experiences and knowledge to understand what we are listening to and what features are most important to figure out the intended message. However, children do not have the same acquired experiences with the world as adults—so, it is important to know how they understand the world differently. “Our study is the first step toward understanding how kids tell apart speech and song, but future studies can suggest how to teach children how to quickly recognize that they are listening to speech or song, so they can then use that knowledge to guide their attention toward relevant information depending on the context,” said Dr. der Nederlanden.

Dr. Vanden Bosch der Nederlanden also described that researchers can use the auditory features that children do pay attention to and use those to support learning in children who struggle with language processing. Not only do individuals with dyslexia encounter trouble when hearing speech sounds, but they also struggle with rhythm and timing in music. As Dr. der Nederlanden explains, “[Children] aren’t able to reliably keep time themselves. In that way, music could act as a scaffold for speech processing, providing an external beat that dyslexic individuals could rely on to extract speech sounds occurring at highly predictable moments in time.”

Dr. der Nederlanden also noted the larger context for this research, saying that this study “relates to lots of big questions about whether we are born with special areas of the brain dedicated to processing speech, or whether we develop specialized processing of speech through our experiences learning what is or is not speech.” It is often the littlest kids among us that can help shed the most light on the big questions in Psychology!

Currently Dr. der Nederlanden’s LAMA Lab plans to start new research for infant, child, and adult studies after the grand opening of the lab’s new space this Spring. The lab invites you and your child to participate in this new and exciting research. After all, Dr. der Nederlanden mentioned that “our work depends on the generosity of people in our community.”

Have your little explorer join the LAMA Lab for our future adventure! Visit: www.utmlamalab.com to find out more!

Vanden Bosch der Nederlanden, C. M., Qi, X., Sequeira, S., Seth, P., Grahn, J. A., Joanisse, M. F., & Hannon, E. E. (2023). Developmental changes in the categorization of speech and song. Developmental Science, 26(5), e13346. https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.13346